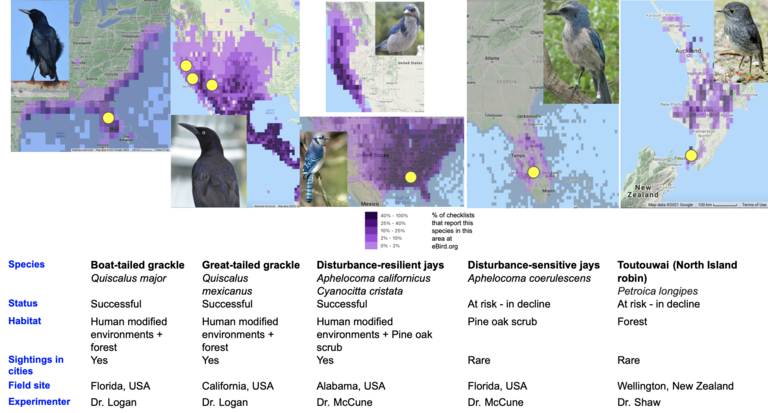

ManyIndividuals – bird field sites in North America and New Zealand

Site Details

I have established three field sites on great-tailed grackles since 2013 at locations across their range to determine whether behavioral flexibility is more prevalent in a northern edge population (Woodland/Sacramento, CA USA, 2020-2022) compared with older populations (Tempe, AZ USA, 2017-2020; Santa Barbara, CA USA, 2014-2015). In 2022, I established a field site on closely related boat-tailed grackles, which are not rapidly expanding their geographic range like the great-tails are, to determine whether great-tails are more flexible than boat-tails (Venus, FL USA, 2022-current).

I am collaborating with my co-founders of ManyIndividuals, Dr. Kelsey McCune and Dr. Rachael Shaw, who are conducting the same experiements at their field sites in Wellington, New Zealand (toutouwai), Archbold Biological Station in Venus, FL USA (Florida scrub-jays), and Auburn, AL USA (blue jays).

Research

What is behavioral flexibility and is it a mechanism for surviving in new environments?

Behavioral flexibility, the ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances, is thought to play an important role in a species' ability to successfully adapt to new environments and expand its geographic range. However, flexibility is rarely directly tested in species in a way that would allow us to determine how flexibility works and predict a species' ability to adapt their behavior to new environments. I use great-tailed grackles (an urban bird) as a model to investigate this question because they have rapidly expanded their range into North America over the past 140 years. In Santa Barbara, I found that they are behaviorally flexible and that flexibility is independent from problem solving ability, problem solving speed (Logan 2016a), other behaviors (Logan 2016b), and innovativeness (Logan 2016c), and that grackles can solve some problems with a similar efficiency to New Caledonian crows (Logan et al. 2014).

I am currently investigating how great-tailed grackles are able to rapidly expand their geographic range by testing their behavior, immunity, hormones, parasites, and population genetics in two populations: an older and a newer population. So far, we found that we can manipulate flexibility through serial reversal learning and that this manipulation makes individuals more flexible and more innovative in a new context (a puzzlebox). We also found that reversal learning (a measure of flexibility) positively correlates with performance on the go/no go task (a measure of inhibition), and has no relationship with detour performance (a measure of inhibition) or causal cognition (there was no evidence of causal cognition, though this could be due to our experimental design). Contrary to most bird species studied so far, great-tailed grackles show male-biased dispersal. We discovered the second case of male parental care in great-tailed grackles and are seeing this behavior in multiple locations. The one male-juvenile pair we were able to catch showed that they are not genetically related, indicating that the caring male was not contributing to his direct fitness and instead might perform this behavior as a result of uncertain paternity or as a signal to future mates.

Does increasing behavioral flexibility increase success in human modified environments? (ManyIndividuals)

I co-founded a global network of researchers with field sites to investigate hypotheses that involve generalizing across many individuals. We conduct the same tests in the same way across species to determine whether the results of particular experiments are generalizable beyond that species. We are manipulating behavioral flexibility in species that are successful in human modified environments (great-tailed grackles and blue jays) and in endangered species (Florida scrub-jays and toutouwai) to determine whether an increase in flexibility improves their success in human modified environments. Follow the link to learn about our open, verifiable, and replicable workflow that makes our research better and faster.

Selected Publications

Summers J, Lukas D, Logan CJ, Chen N (2023). The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pair. doi: 10.32942/osf.io/879pe

Pacheco MA, Ferreira FC, Logan CJ, McCune KB, MacPherson MP, Albino Miranda S, Santiago-Alarcon D, Escalante AA (2022). Great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus) as a tolerant host of avian malaria parasites. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268161

Sevchik A, Logan CJ, McCune KB, Blackwell A, Rowney C, Lukas D (2021). Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal. doi: 10.26451/abc.09.01.04.2022

Blaisdell AP, Seitz B, Rowney C, Folsom M, MacPherson M, Deffner D, Logan CJ (2021). Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed grackles. doi: 10.24072/pcjournal.44

Logan CJ, McCune KB, MacPherson M, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Rowney C, Seitz B, Blaisdell AP, Deffner D, Wascher CAF (2021). Are the more flexible individuals also better at inhibition? doi: 10.26451/abc.09.01.03.2022

Seitz BM, McCune KB, MacPherson M, Bergeron LM, Blaisdell AP, Logan CJ (2021). Using touchscreen equipped operant chambers to study comparative cognition. Benefits, limitations, and advice. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246446

Logan CJ. 2016. Behavioral flexibility and problem solving in an invasive bird. doi:10.7717/peerj.1975

Logan CJ. 2016. Behavioral flexibility in an invasive bird is independent of other behaviors. doi: 10/c598

Logan CJ. 2016. How far will a behaviourally flexible invasive bird go to innovate? doi: 10/c599