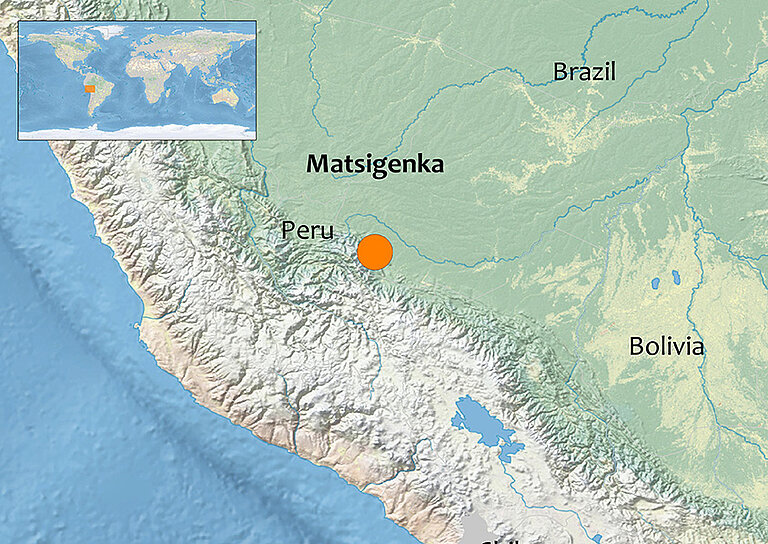

Matsigenka and Colonos – Lowland, Peru

all pictures: © John Bunce and Caissa Revilla Minaya

Description

Principle investigators:

John Bunce, Caissa Revilla MinayaTeam members:

Catalina Fernández HernándezResearch since: 2010

Site Details

The Matsigenka are a lowland Amazonian indigenous group of Southeastern Peru whose language is part of the Arawak language family. The population of approximately 1000 (contacted and “uncontacted”) people who live in the tropical forests of the Manu River basin inside Manu National Park practice swidden horticulture (growing primarily manioc and plantains), as well as hunting, fishing, and gathering. In Manu, Matsigenka social life is generally organized around the clan (extended family), which is usually matrilocal (but with increasing exceptions), with clearly-defined gender and age-specific roles. Matsigenka of the region were persecuted and enslaved during the Rubber Boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and many fled deep into the headwaters of the Manu and Urubamba river systems to escape slave raids. An unknown (to us) number of these Matsigenka in “voluntary isolation” still reside there. The evangelical Christian Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) arrived in the region in the 1960s and attracted many Matsigenka families from the headwaters to settle in the community of Tayakome, on the Manu River, where they offered Western schooling, healthcare, and access to Western goods. SIL was expelled from region when Manu National Park was founded in 1973.

This UNESCO World Heritage site is one of the largest national parks in Amazonia and contains some of the world’s highest biodiversity. Under Peruvian law, people living inside protected natural areas may remain if they were living in the area before protected status was bestowed. However, they are subject to certain restrictions. The Matsigenka of Manu are allowed to stay in the Park only if they maintain “traditional” subsistence activities, which are defined (by the Park) to preclude the use of firearms, domesticated animals (other than chickens and dogs), and the sale of anything produced inside the park (excepting handicrafts). These restrictions are a continuing source of tension. Currently, the Peruvian State maintains health posts, as well as kindergartens and primary schools in some communities. Many Matsigenka work for several months of the year outside the Park in tourism and logging, and many children attend boarding secondary schools outside the park. Matsigenka residents may leave and return to their communities inside the Park anytime they wish, provided they have community authorization. However, non-Matsigenka may only enter the Matsigenka communities temporarily on official business, and with the authorization of the communities themselves and the Park administration.

Surrounding Manu National Park are a number of non-indigenous towns, as well as Native Communities of Matsigenka, Yine, and Harakmbut who hold official title to their land. Residents of non-indigenous towns include many people who migrated down from the Andean region (especially the Departments of Cusco, Puno, and Apurimac) to colonize the lowlands starting around the 1940s, as well as their descendants, and a few local indigenous people, including Matsigenka. For convenience here, we label non-local residents as “Colonos” (colonists), although most don’t consistently use any single term to refer to themselves. Life in Colono towns is focused around the nuclear family, whose members engage in small-scale economic activities, including tourism for the park, attending small general stores, logging, cash-cropping (mostly plantains), and boat-building. Most residents maintain strong family and economic ties with distant urban centers, such as Cusco and Puerto Maldonado. Many of the wealthier residents visit these cities regularly for healthcare needs and send their children to be educated there, despite the presence of local health posts, and primary and secondary schools in the towns. More information about the Matsigenka and Colonos can be found in the publications below.

Research

John studies cultural dynamics in the Matsigenka and Colono populations. He is particularly interested in cultural norms, i.e., peoples’ beliefs about what constitutes appropriate behavior in contexts such as child-rearing, inheritance, labor, healthcare, and education. We have shown, unsurprisingly, that Matsigenka and Colonos tend to hold different norms in many such contexts. However, the distributions of these norms will almost certainly change over time, especially for the Matsigenka, as their interactions with Colonos outside the park in contexts such as commerce, wage labor, and education steadily increase. Our research suggests that certain types of Matsigenka-Colono inter-ethnic interaction, such as boarding secondary-school education, may have a stronger effect on the loss of Matsigenka-typical cultural norms than do other forms of inter-ethnic interaction, such as wage labor. We developed several hypotheses to explain the observed pattern of norm distributions, including differences in the bargaining power of Matsigenka relative to Colonos during individual-level coordination interactions. To test these hypotheses, we are conducting a longitudinal study of cultural norms and inter-ethnic interaction in the Matsigenka and Colono communities, as well as among Matsigenka boarding-school students and their teachers in Colono towns. One goal of this work is to contribute to a robust mechanistic theory of cultural change at ethnic boundaries. A second, and equally important, goal is to empower minority ethnic groups, like the Matsigenka, to develop strategies for the sustainability of cultural norms that they, collectively, would like to preserve, while at the same time facilitating desired inter-ethnic engagement.

Caissa’s research interests are related to human conceptualizations of, and interactions with, the environment. In particular, her study among the Matsigenka of Manu explores cultural understandings of non-human beings and the role of these understandings in people’s environmental behavior. Her research employs mixed methods, combining qualitative ethnographic and quantitative data collection, to examine the population-level variability and distributions of Matsigenka notions of plants, animals, and other non-human beings, as well as the dynamics of cultural change. She plans to complement her current research by studying these notions among residents of the non-Matsigenka Colono towns around Manu National Park, as well as by studying the processes of acquisition and transmission of environmental conceptualizations, in order to explore the mutual cultural influence of Matsigenka and Colonos. Caissa is also interested in exploring how environmental conflicts that emerge in particular socio-political contexts may be related to encounters between people with conflicting conceptions of the world, and the practices associated with such conceptions.

A common theme for the research agenda we have developed at this field site relates to gaining a deeper understanding of the complex interactions between changing cultural norms, environmental knowledge, and behaviors, particularly in societies with low-intensity integration into the global market economy.

With this goal in mind, in November 2020 we established the Culture, Environment, and Health Research Group, with our postdoc Dr. Catalina Fernández, who started at the end of 2020 (with a 1-year gap due to maternity leave). Prior to joining our group, Catalina conducted research on the topic of the evolutionary mismatch between long-term adaptations and changing environmental conditions among contemporary indigenous communities in Chile. She continues this work in parallel with our current projects.

In our group, we investigate how the dynamics of cultural norms, perceptions of the environment, and subsistence practices impact health and concepts of wellbeing. Our first objective is to understand how inter-group interaction affects health, as mediated through environmental perceptions, thereby shedding light on its important role in the evolutionary history of our species. A second objective is to better understand the healthcare needs of local communities, paying attention to their particular conceptions of wellbeing. This work, however, requires long-term ethnographic fieldwork, which was unfeasible until the end of 2022 due to travel and local restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. In January 2023, John and Caissa were able to return to the Matsigenka communities, where we began a new empirical study of energy expenditure, caloric intake, and perceptions of dietary change and wellbeing, testing new data collection techniques tailored to the Matsigenka context. For this project, Catalina contributes her particular expertise, and a comparative perspective, on the foodways, nutrition, health and wellbeing of diverse human populations.

Figure 23. Estimated height and weight trajectories. Shown are posterior estimates from the composite height (upper row) and weight (lower row) growth models fit to temporally-dense measurements from U.S. children (red), and temporally-sparse measurements from Matsigenka children (blue). Thin lines are mean posterior trajectories for each individual. Thick red and blue lines are mean posteriors for the mean cumulative trajectories of each ethnic group, as well as the trajectories within each of the three growth phases: infancy, childhood, and adolescence. Corresponding mean posterior mean cumu-lative velocity trajectories in green and orange are decreasing (after age 14) from left to right. From Bunce, Fernández and Revilla Minaya (2022 preprint)

Simultaneously, John, Caissa, and Catalina developed new hypotheses and theoretical mathematical models to study physiological traits that may reflect environmental conditions and cultural changes particular to individual human populations. Using data on age, weight and height collected in previous field seasons among the Matsigenka, together with previously published data from other populations, we developed new models to estimate and compare growth trajectories within and across populations according to growth phase-specific genetic and environmental factors. We interpret these results in light of particular dietary and lifestyle factors of each population. This analysis is currently in the preprint stage. In the coming months, our plan is to apply these models to a worldwide cross-cultural comparison of growth trajectories, collaborating with a network of anthropological fieldworkers to incorporate data from small-scale populations in a wide range of ecologies and market integration contexts. Our aim is to better understand causes of global variation in the tempo and magnitude of growth in our species. Such an understanding will, ideally, allow us to suggest strategies to design better healthcare and nutritional interventions that are effective, culturally sensitive, and population-specific.

Selected Publications

Bunce, J. A., & Revilla-Minaya, C. (in preparation). Quantifying the effect of inter-cultural secondary-school education on cultural change in an Amazonian indigenous population.

Revilla-Minaya, C. (in preparation). Persons, agents, objects and everyone in between: Diverse perspectives of non-human beings in a Matsigenka community in Peru.

Fernández, C. I., Revilla-Minaya, C., & Bunce J. A. (in preparation). Metabolism and allome-try: A large-scale cross-cultural study of child growth.

Bunce, J. A., & McElreath, R. (in press). Ethnicity and cultural dynamics. In R. Kendal, J. Kendal, & J. Tehrani (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Cultural Evolution. Oxford University Press.

Bunce, J. A., Fernández, C. I., & Revilla-Minaya, C. (2022 preprint). Causal models of human growth and their estimation using temporally sparse data.

Revilla-Minaya, C., & Bunce J. A. (2022). Una experiencia contemporánea matsigenka de una epidemia local (A contemporary Matsigenka experience with a local epidemic). In O. Espi-nosa, E. Fabiano (Eds.), Las Enfermedades que Llegan de Lejos: Los Pueblos Amazónicos del Perú Frente a las Epidemias del Pasado y a la COVID-19 (Diseases That Come From Afar: Amazonian Peoples of Peru in the Face of Past Epidemics and of COVID-19), 449-458. Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima.

Bunce, J. A. (2021). Cultural diversity in unequal societies sustained through cross-cultural competence and identity valuation. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8: 238.

Broesch, T., Crittenden, A. N., Beheim, B. A., Blackwell, A. D., Bunce, J. A., Colleran, H., Hagel, K., Kline, M., McElreath, R., Nelson, R. G., Pisor, A. C., Prall, S., Pretelli, I., Purzycki, B., Quinn, E. A., Ross, C., Scelza, B., Starkweather, K., Stieglitz, J., & Borgerhoff Mulder, M. (2020). Navigating cross-cultural research: methodological and ethical considerations. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 287: 20201245.

Bunce, J. A. (2020). Field evidence for two paths to cross-cultural competence: implications for cultural dynamics. Evolutionary Human Sciences, 2(e3):1-16.

Revilla-Minaya, C (2019) Environmental Factishes, Variation, and Emergent Ontologies among the Matsigenka of the Peruvian Amazon. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA. [Link]

Bunce, JA and R McElreath (2018) Sustainability of minority culture when inter-ethnic interaction is profitable. Nature Human Behaviour 2:205-212. [Link]

Bunce, JA (2018) Field evidence for two paths to cross-cultural competence: implications for cultural dynamics. SocArXiv. December 7. doi:10.31235/osf.io/468ns. [Link]

Bunce, JA and R McElreath (2017) Inter-ethnic interaction, strategic bargaining power, and the dynamics of cultural norms: a field study in an Amazonian population. Human Nature 28(4):434–456. [Link]

Bunce, JA (2014) Creating one’s own postdoc position: an NSF-funded investigation of cultural change in Amazonia. Anthropology News 55(7):e18-19.