Thermal Imaging

The surface temperature of objects, as well as living beings can be measured from a distance without direct contact using infrared thermal cameras. These cameras record the corresponding temperature value for each pixel in an image and, via several postprocessing steps, we can determine how the temperature within an area of interest changed over the course of the video.

Why are we interested in temperature measurements in the field of comparative psychology?

The temperature of certain areas of the human skin – even under constant weather conditions – fluctuates continuously. These fluctuations are related, at least partly, to changes in autonomic nervous system activity and hence depend on the emotions we are experiencing. For example, when we feel stress, fear, or guilt, the temperature of the nose falls. The same effect has been documented when we observe someone close to us in an unpleasant situation, or when we perform a challenging mental task. However, strong positive emotions such as joy (while we laugh heartily) can also lower the temperature of the nose.

The first thermal imaging studies with non-human primates have shown that emotions also affect the nose temperature of apes. Chimpanzees at Leipzig Zoo, for example, were played recordings of fellow chimps fighting. In response, the nose temperature of the apes dropped by several degrees Celsius (Kano et al., 2016). Similar findings have been obtained from chimpanzees in the wild (Dezecache et al., 2017). This shows that chimpanzees generally find it very exciting to watch fights between fellow chimps. In another study, chimpanzees witnessed how a human they knew (seemingly) accidentally injured themselves (Sato et al., 2019). Here, too, we could observe a drop in nose temperature, which suggests that the animals may have felt some kind of empathy with the human, or that observing the injury at least generated some agitation. There is also initial evidence that strong positive emotions, such as when playing exuberantly, lead to a reduction in nasal temperature in apes (Chotard et al., 2018; Heintz et al., 2019).

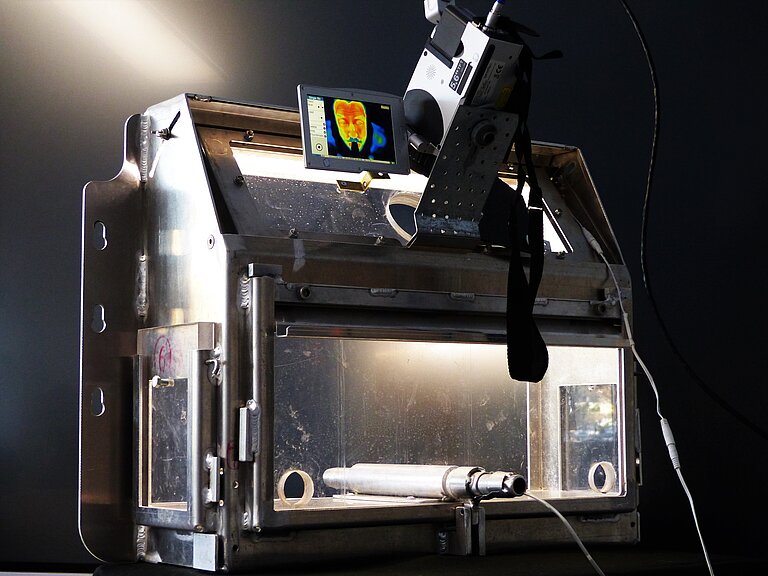

Thermal imaging thus enables us to gain insights into the emotional world of our closest living relatives in a contact-free and non-invasive way. Because the technology is flexible and mobile, we can conduct nose temperature measurements in a wide variety of situations: In response to video stimuli in a controlled study setup as well as during natural interactions between apes in their social group.

We aim to further establish thermal imaging in research with great apes, thereby gaining more knowledge about the emotions of chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orang-utans. This newly gained knowledge will enable us to learn more about the evolutionary origins of our own emotional world.

world.